Cities tend to be warmer than the surrounding countryside, a phenomenon known as an urban heat island (UHI). This happens because concrete, asphalt and shingled roofs absorb heat more easily than fields and forests, then hold on to this heat more effectively at night than the surrounding countryside – which usually has more vegetation and trees.

Click here for the interactive version >>

What that means is that as summers get hotter under the planet’s growing blanket of heat-trapping greenhouse gases, the worst of it will happen downtown rather than out of town. Climate Central’s new analysis of the UHI effect in 60 of the largest continental U.S. cities makes it clear just how big the gap can be during the summer. Over the past 10 years, the cities were 2.5°F hotter, on average, than in nearby rural areas. But in Albuquerque, the difference was 5.9°F, and Las Vegas topped our list with a difference of 7.3°F.

Because cities don’t cool as easily as their surrounding areas after sunset, the nighttime differences were even greater: 4°F on average, with Las Vegas topping out at 10.3°F, followed by Albuquerque at 9.7°F and Portland, Ore., at 8.9°F. Single-day differences were sometimes dramatically greater. In 23 cities, urban-rural high temperatures differed by more than 20°F at least once.

Another way to look at urban heat islands is to analyze how many more extremely hot days were recorded in the city vs. the outlying areas. We define extremely hot days as those above 90°F in most parts of the country, and above 100°F where it’s normally very hot to begin with. In the analysis, there were 47 cities where temperatures exceeded 90°F more frequently in the cities than in nearby rural areas, and there were 25 cities where urban stations exceeded 90°F at least 10 days more each year, on average, than their rural counterparts. Also, cities average eight additional days above 90°F than surrounding areas.

The difference between urban and surrounding rural temperatures is also widening. In 45 of the 60 cities we studied, temperatures have been rising in urban areas faster than in the surrounding rural areas since 1970.

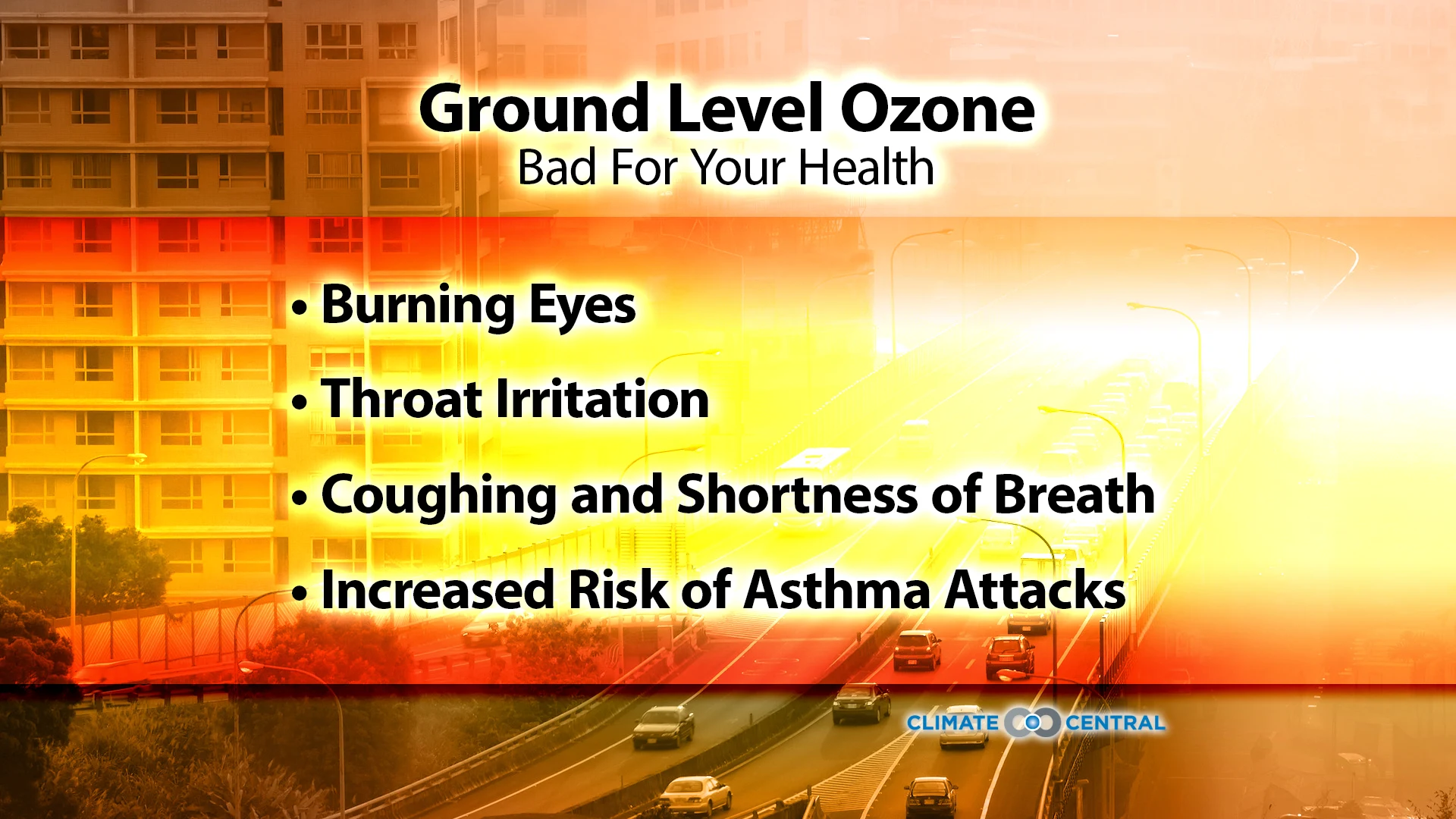

The most obvious consequences of higher temperatures are discomfort and increased energy usage for air conditioning. More energy also means more greenhouse-gas emissions, especially for places that rely on coal to generate electricity. But higher temperatures also take a toll on human health. Heat itself is one of the leading weather-related killers, and it’s also a significant contributing factor in creating ground-level ozone, which is a serious health hazard.

In the upper atmosphere, ozone is a good thing. It shields the Earth from harmful ultraviolet rays from the sun (that’s why the so-called “ozone hole” over Antarctica is cause for concern). Close to the ground, however, ozone contributes to an increased incidence of lung inflammation, asthma attacks, and other respiratory problems, particularly in children and young adults. For that reason, our new report also looks at the relationship between heat and ozone levels.

For this week’s Climate Matters, we analyzed ground-level ozone data for your market or the nearest big city to your market (if there wasn’t reliable data for your particular city). You will see that as temperatures go up, ground-level ozone goes up, making for poorer air quality. A lot of factors influence ground ozone but sunlight, heat, and air pollution are three of the biggest. As temperatures continue to rise, it’s going to make it more difficult to meet ozone standards.